This week, I had the pleasure of guest-hosting the Girard at Large television show with Ian Underwood. Ian is an education advocate who has a unique and persuasive take on education reform.

Read This First

I want to make sure you don’t waste your time reading this article. For that reason, I developed a one-question test you can take to determine if you are ready to have this discussion:

Do you agree that a “fair” system is one that provides the same education to everyone – no more and no less?

If you answered, “Yes,” then you should proceed with the rest of the article. If you answered, “No,” you will be wasting your time.

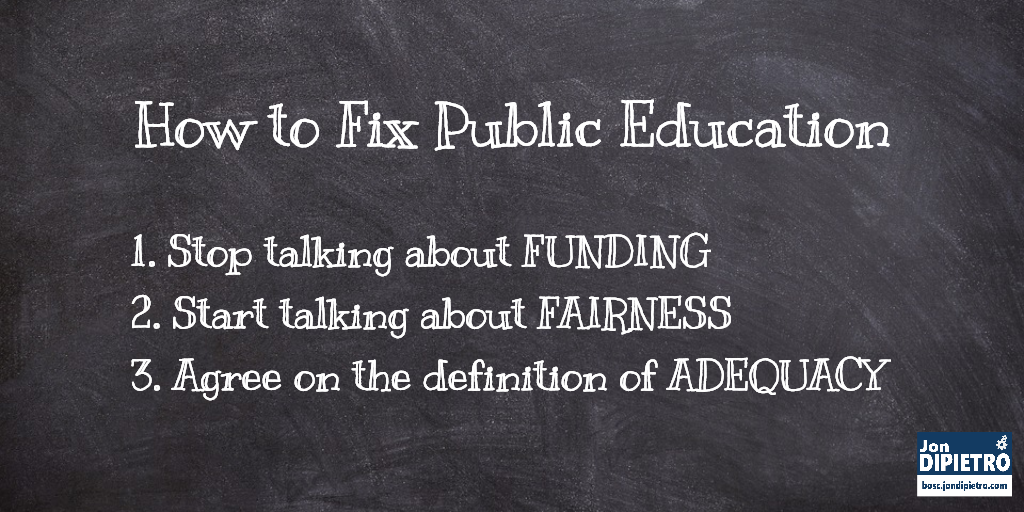

The solution to public education can be summarized as:

- If your objective is fairness in education, funding is the wrong discussion.

- A system that is based on time instead of adequacy is inherently unfair to everyone involved: the taxpayers and the students.

- As soon as we begin to focus on literacy, numeracy, and rationality instead of funding, we’ll be on the cusp of fixing public education.

1. Stop Talking About FUNDING

For some reason, most people seem to accept that funding and fairness and adequacy in education are all the same thing without a single critical thought on the matter. They are not the same and I will prove it.

Therefore, if your objective is fairness in education, funding is the wrong discussion.

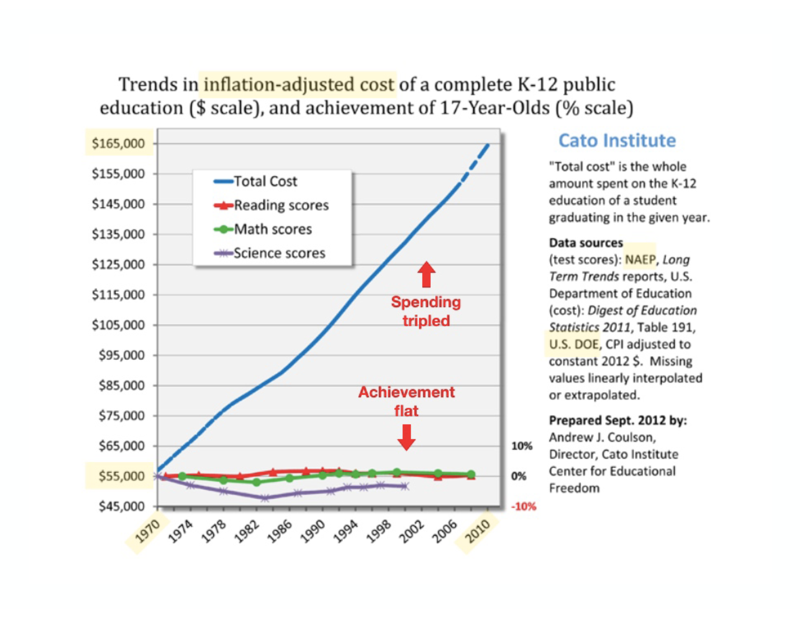

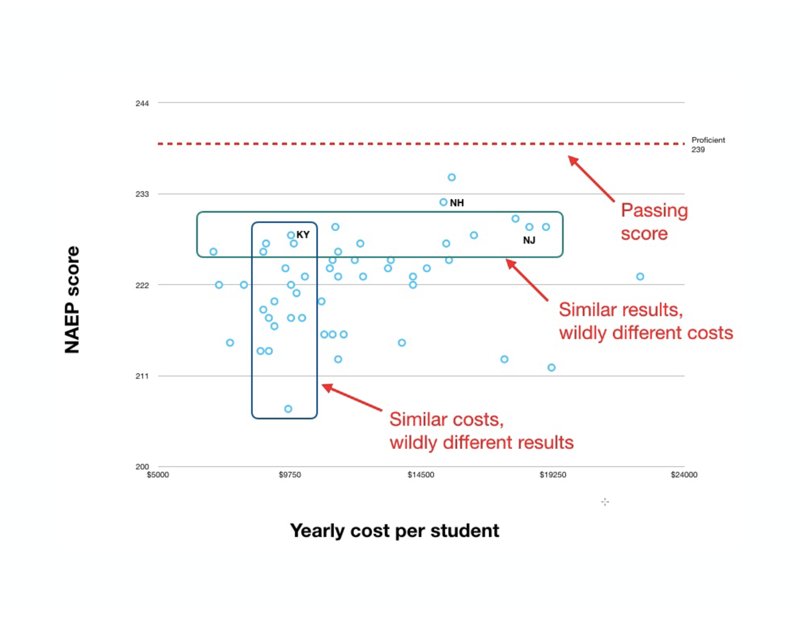

Here are 3 charts that illustrate why funding has nothing to do with outcomes or fairness…

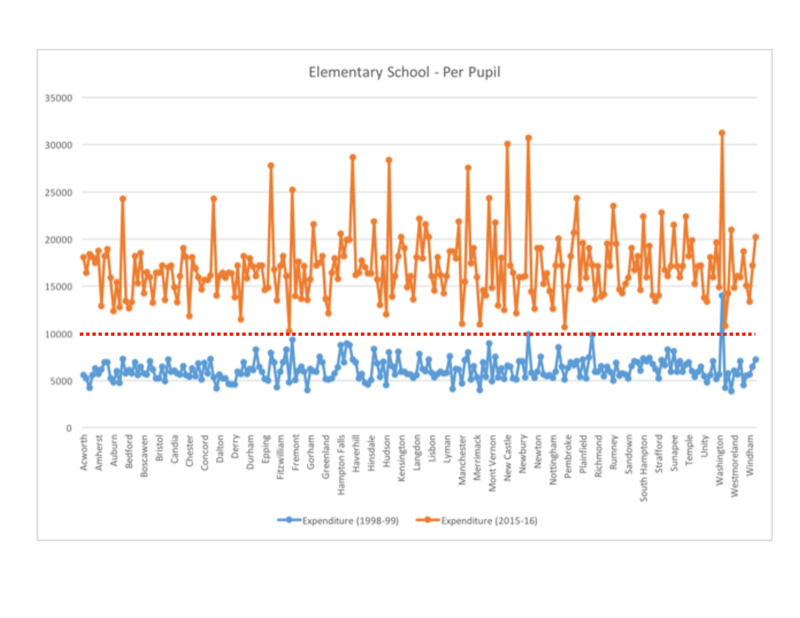

These charts prove that the level of funding has no correlation whatsoever to education outcomes. As a country, we’ve tripled education spending and have nothing to show for it. When examining NAEP scores (considered to be the nation’s report card), we see that some states spend wildly different amounts of money while seeing the same results. We see other states spend similar amounts of money while seeing wildly different results.

This last graph is provided in order to dispel the myth that education funding hasn’t increased substantially. With one exception, every single school district in the state of NH has increased their per-pupil spending since the Claremont decision.

So if funding is the wrong discussion, what is the right one?

2. Start Talking About Fairness

If you agree with the premise that a “fair” system provides every student with the same education, no more and no less, then it’s worth asking ourselves, “Fair to whom?”

“No more” means it’s fair to the taxpayers. “No less” means it’s fair to the students. Everyone wins. But that’s not how the system currently works.

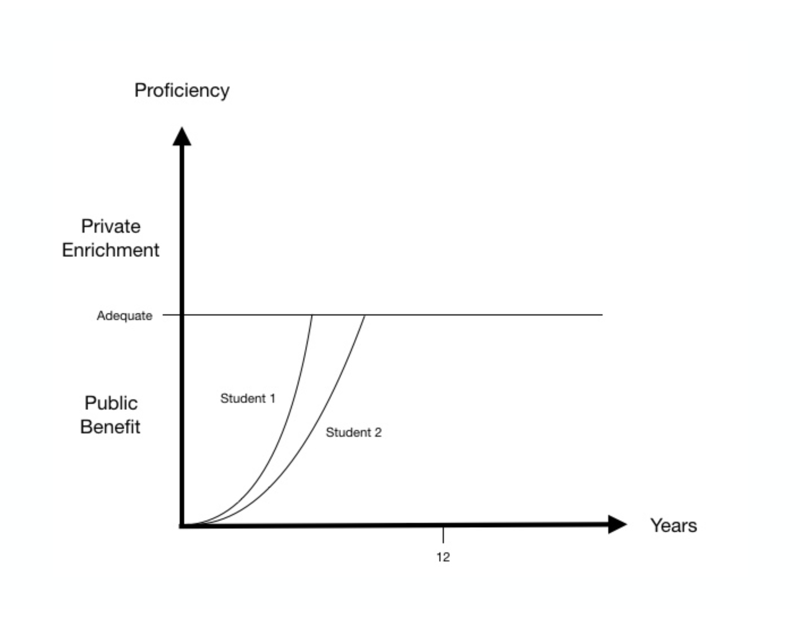

Our education system is currently based entirely on seat time. Students occupy space for 12 years and we pretend that that’s a fair system. It would be hilarious if it were not so tragic.

Compare Student 1 and Student 2. Over a period of 12 years, Student 1 learns at an accelerated rate and finishes far above the line for adequacy. Student 2, on the other hand, learns more slowly and graduates nowhere near the adequacy line.

The Student 1 scenario is unfair to the taxpayer. They are subsidizing more than is necessary. The Student 2 scenario is unfair to the student. She is not afforded an adequate education.

A system that is based on time instead of adequacy is inherently unfair to everyone involved: the taxpayers and the students. Everybody loses.

So what would a fair system look like?

If our education system focused on ensuring every student received an adequate level of proficiency, it would look something like this:

We now know that funding is the wrong conversation and fairness is the right conversation. It’s time to address the final step in fixing public education.

3. Agree On the Definition of Adequacy

While the first two steps are on solid objective and logical ground, the third step is more subjective and arguably requires a deeper conversation. To do that constructively, we need a framework.

What is the goal of public education? You can’t establish a definition of adequacy without first knowing what the goal is. One popular view is that “the true purpose of education is to produce citizens.” It’s critical that we agree on this, particularly in light of the fact that American schools were founded at the dawn of the industrial age to be workforce training centers. As we stand at the dawn of the information age, it’s neither practical nor necessary for public schools to focus on workforce development. With the ubiquity of the Internet, everything a citizen ever wanted to learn is available within seconds for free.

But one needs three skills to take advantage of these opportunities and they happen to be the same skills that produce good citizens:

- Literacy

- Numeracy

- Rationality

Taxpayers have a vested interest in preventing its citizens from illiteracy, innumeracy, and irrationality. All of these things make a representative democracy harder and more expensive to operate. With these criteria in hand, we can now begin to establish a framework for defining adequacy.

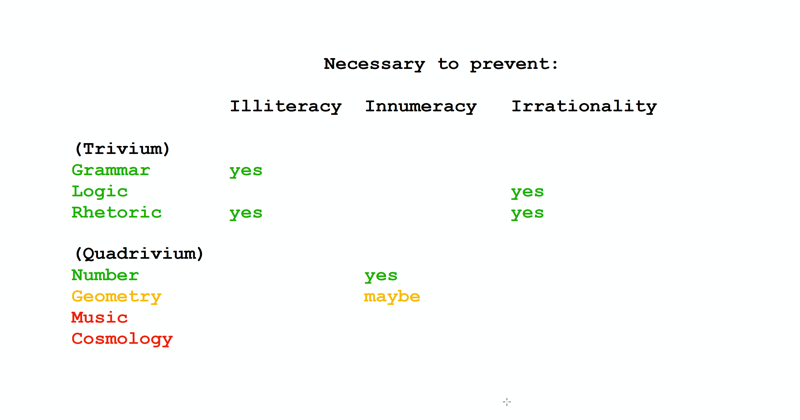

Classical Liberal Arts

A liberal arts education consists of seven subjects, divided into two parts: the Trivium and the Quadrivium. The Trivium consists of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, while the Quadrivium consists of arithmetic, astronomy, music, and geometry. If we create a matrix and compare these seven subjects to our three criteria, it looks like the following:

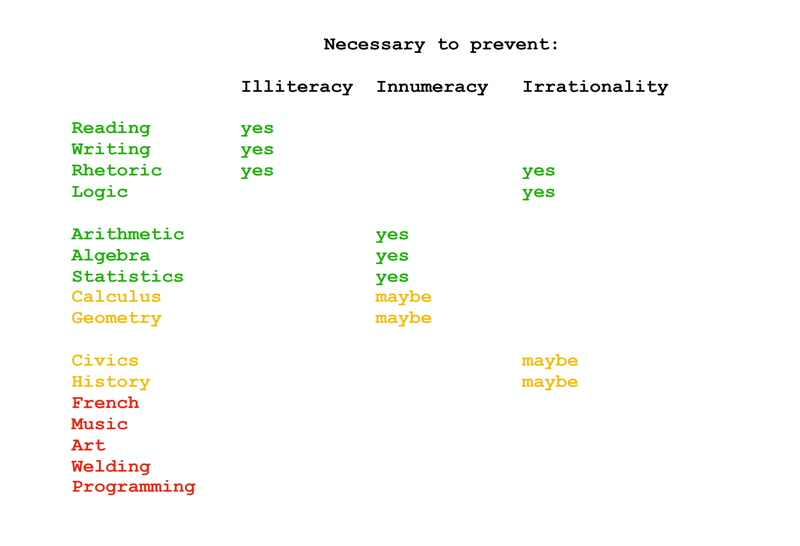

We see that all three subjects of the Trivium are relevant to our criteria while two from the Quadrivium are not and one is debatable. Now let’s take a look at how many common high school subjects stack up against our adequacy criteria:

This is where the discussion will almost certainly become contentious. Removing foreign languages, music, and art will be controversial and that’s understandable. But it’s also the final step in the solution and we are currently miles and miles away from even being able to begin this discussion.

As soon as we begin to focus on literacy, numeracy, and rationality instead of funding, we’ll be on the cusp of fixing public education.

Abolition. Nothing else will work. The “schools” are doing exactly what they were designed to do, trying to fix them is a fool’s errand.